Rising above our Biology

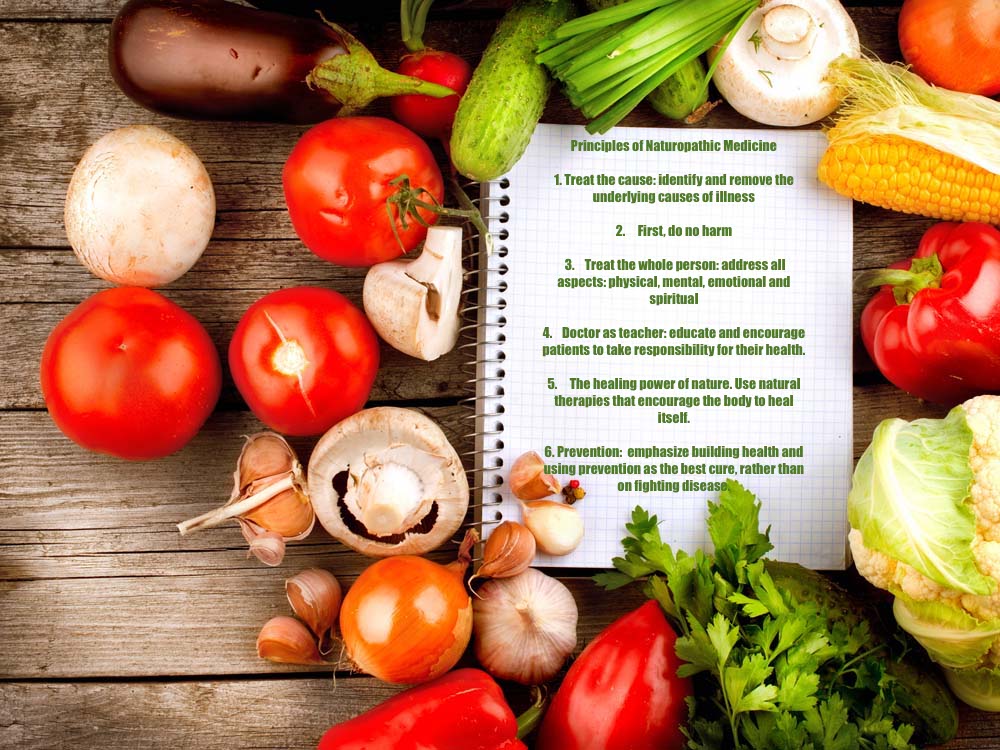

When trying to answer the question, “Why am I the way I am?” it is important to try to identify the root causes of when things began. This is a primary tenet of naturopathic medicine.

For some individuals—and often in the case of adoption—it is important to go back to when you were in utero to understand certain things about yourself. It is at this early time that neurological and emotional wiring begins; therefore, the mental and emotional state of your mother (or the person who carried you to birth, in the case of adoption or surrogacy) contains important biological imprinting. Dr. Gabor Maté discusses this in his book In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts—Close Encounters with Addiction. He writes:

“In the past few decades it has become increasingly clear that the development and later behaviour of an immature organism is not only determined by genetic factors and the postnatal environment, but also by the maternal environment during pregnancy.

Numerous studies in both animals and human beings have found that maternal stress or anxiety during pregnancy can lead to a broad range of problems in the offspring, from infantile colic to later learning difficulties and the establishment of behavioural and emotional patterns that increase a person’s predilection for addiction. Stress on the mother would result in higher levels of cortisol reaching the baby and elevated cortisol is harmful to important brain structures, especially during periods of rapid brain development.

Any woman who has to give up her baby for adoption is, by definition, a stressed woman. She is stressed not just because she knows she’ll be separated from her baby, but primarily because if she wasn’t stressed in the first place, she would never have had to consider giving up her child: the pregnancy was unwanted, or the mother was poor, single or in a bad relationship, or she was an immature teenager who conceived involuntarily, or was a drug user or was raped or confronted by some other adversity.

Any of these situations would be enough to impose tremendous stress on any person, and so for many months, the developing fetus would be exposed to high cortisol levels through the placenta. A proclivity for addiction is one possible consequence.”

In my case, my biological mother became pregnant with me when she was 16. I don’t know the circumstances surrounding my conception, except that because of her family’s religion—Irish Catholic—abortion was not an option. Her parents moved her to the other side of the country—from Grand Falls, New Brunswick to Vancouver, British Columbia—where she lived with her older sister until it was time to give birth.

Given the research cited above, it is likely that the stress my biological mother was under exposed me to cortisol, the stress hormone, at higher levels than would be experienced in planned pregnancies. As a newborn, I didn’t sleep well from the beginning—something that I would make up for during many depressive episodes later in life when all I did was sleep the days and months away.

Attachment issues The way I found out I was adopted didn’t help me to attach securely to my parents. According to the attachment theory of parenting, we are all creatures of attachment which means that what we all want most is connection, attachment and relationship, whether as a child or as an adult. What a child wants more than anything is a connection to their parent, even when there is no resemblance. Given how I learned that I was adopted, I feel it left me feeling insecure about my place in the family. Essentially, when my mom explained the word “adopted” to me, my young brain interpreted it to mean “temporary.”

As adults, we tend to assume our children understand the meaning of the words we use, but in many cases, they misconstrue it. In my case, we had watched a movie at school showing animals with their offspring, and this got me thinking about where human babies came from. The advice my parents had been given by a social worker in the late 1960s was to tell me the truth about my origins whenever I eventually asked where babies came from. After watching the movie, I went home from school curious about babies and inquisitively asked about how I came to be. My parents took this opportunity to explain that I was adopted. I internalized their explanation by assuming that I was only with them temporarily, and that some day, my “real” mom would be coming to get me.

Consequently, every time the doorbell rang or my mom started talking to someone I didn’t recognize at the store, I would wonder, “Is this the person who is coming to get me?” The years went by and no one came. I think I was 12 years old when I finally asked my mom if anyone was ever coming. Naturally, she was dismayed when she realized what had happened.

For me, learning that I was adopted, from the way I processed it to the negative comments from some family members to my parents—such as “blood is thicker than water”—cast a belief in me that I wasn’t good enough or truly wanted. It fed my insecurities, which played themselves out on the school grounds, as I was a prime target for kids to pick on. And I did get picked on—so much so that my mom had to find a job at the school so that I had more support than the teachers were able to give me. Some girls in my grade four class started an “I hate Christina” club, and this devastated me. (The funny thing is, the same thing happened to my son when he was in grade two. My heart sank when he told me. But his response highlights the difference between poor self-esteem, which I had at his age and self-confidence, which he has, as he said: “It’s okay mom—no one joined!”)

Despite my insecurities around adoption and being picked on in elementary school, there were no other traumas in my childhood. I was fortunate to be adopted into a loving family with caring parents. We moved a few times, which taught me to be resilient and accepting of others. All was well until I became a teenager and developed an eating disorder around the time my parents were getting divorced. It was then that the crack in my emotional foundation deepened.

I think the low self-esteem I had came from in utero based on the research cited by Dr. Gabor Mate. The energetics of adoption are complicated. Given the thoughts my biological mother was processing at the time and the probable trauma, scandal and embarrassment she endured for being pregnant out of wedlock at a time when this was not accepted, would have predisposed me to higher levels of cortisol as compared with a planned pregnancy. The predicament she found herself in affected my neurobiology on a deep primal level. This essentially wired me a certain way – to be insecure, anxious, sensitive, and feel like I wasn’t worthy, wanted or loved. Despite my parent’s best efforts to love me, the deeply profound sense of displacement I felt my whole life was coming from within – it was due to the faulty wiring or programming/messaging I received in utero.

The good news is I have been able to rewire my brain thanks to the concept of neuroplasticity. The bad news is this took approximately 30 years to do. I would test people to see if they would stay. I didn’t know how to communicate or express what I was feeling because most of the time I didn’t understand what I was feeling. Part of me speculates if the manifestation of bipolar disorder type 1 was due to the fact that I couldn’t express my feelings so it presented itself as illness in the emotional realm while the root cause came from this spiritual crisis of adoption. It has been said that “adoption is the only trauma in which the adoptee is expected to be grateful”.

I recently turned fifty. As with every birthday in the past, I wonder if my biological mother thinks about me. When I was 25 years old I met her and she told me that she did think if me every year on June 23. I don’t know the circumstances of her labour and delivery with me, whether I was a vaginal or c-section birth or whether she got to hold me in her arms after I was born. I do know that she kept my birth a secret from my half siblings – all of whom were shocked that their mom had a “skeleton in the closet”.

I decided to meet my biological mother because I wanted to solve the genetic mystery of bipolar disorder type 1. I had a list of questions I wanted answered, but I suddenly lost my confidence when I met her. I felt nervous about asking any questions about the circumstances surrounding my birth. My mom had written a card to Joanne, my biological mother, that read:

“Dear Joanne, Thank you for the greatest gift you could give another. All we have done is love Christina and I consider it a privilege to be her mom ~ Warmest regards, Alice.”

While I didn’t get the medical answers I was looking for at that time. I did receive a call a few years later from my half brother that Joanne had been hospitalized and diagnosed with schizophrenia. It was shortly after that that I fell into a deep, dark depression and had attempted to commit suicide. As I was in recovery for several months, I lost touch with my biological family (this was pre-internet and texting days). One day I might return to New Brunswick to find my half sister who said she knew who my biological father was. I have often wondered why I was so curious about meeting only 50% of my genetic history and not the other 50%. I think it has to do with the bondage and biological wiring in utero that I discussed at the start of this article. For more about my recovery from bipolar disorder type 1, as well as depression, anxiety and bulimia, I encourage you to order my book: Beyond the Label: Achieving Mental Wellness with Naturopathic Medicine.